I recently read on the National Rural Health Association (NRHA) website that 66 rural hospitals have closed since 2010. The closure rate is increasing. It was six times higher in 2015 than in 2010. A study the NRHA commissioned revealed that 673 rural hospitals are “vulnerable or at risk for closure.” Of this group, a large number are Critical Access Hospitals (CAH).

I will never forget the first time I set foot in a Critical Access Hospital. I had been doing healthcare design for more than three years but had never been to (nor heard of) a CAH. As I approached the small town, I nearly drove past the facility not recognizing it from the street. So often, I would be looking for an old Hill-Burton cruciform tower; however, this was a one-story brick building that looked like a post office. It was then that I started to realize the importance of these healthcare facilities and the patient populations they care for.

Critical Access designations for hospitals began in 1997 with the Balanced Budget Act. Within this bill were provisions for facilities with limited access that needed to remain open due to the remoteness of its patient populations. I met and worked with a CEO who helped draft the original conditions for CAH status and helped establish the 35-mile rule. The goal of this bill was to help smaller, more remote, facilities stay financially viable in an attempt to keep them functioning. As a condition of participation, hospitals had to meet the following requirements:

- Furnish 24-hour emergency care services seven days a week, 365 days a year.

- Maintain no more than 25 inpatient beds with an additional 10 beds for Physical Rehab or Behavioral Health.

- Have an annual average length of stay of 96 hours or fewer per acute care patient (discharge transfer).

- Be located more than a 35-mile drive from any hospital, or located more than 15 miles from any hospital where there are mountainous terrain or only secondary roads.

Because of the remoteness of many of these facilities, their patient volumes are relatively low and inconsistent. To aid in their financial viability, the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) created a cost structure to keep them solvent. All US hospitals fall into either a PPS (Prospective Payment System) or CAH designation. The CAH designation allows the hospital to provide services at a Cost + model, namely cost + 1% or (101% of reasonable costs). Other benefits include:

- The removal of unreasonable rebuilding restrictions

- Reasonable reimbursement for CRNA services

- Provisions for bed flexibility

- Enhancement of low volume payments

- Ambulance add-on payments

According to the American Hospital Association, “51 million Americans live in rural areas and depend upon the hospital [in their community].” The AMA further tells us that as of April 15, 2015 – 24.7% of Medicare Participating hospitals are Critical Access designated. Some basic national statistics show that there are 1,330 CAHs in the US with the following annual services provided:

- Eight million patients treated in Emergency Departments

- 38 million patients treated as outpatients

- 809,000 patients admitted

- 82,000 babies delivered

(Source: American Hospital Association | United States Census Bureau)

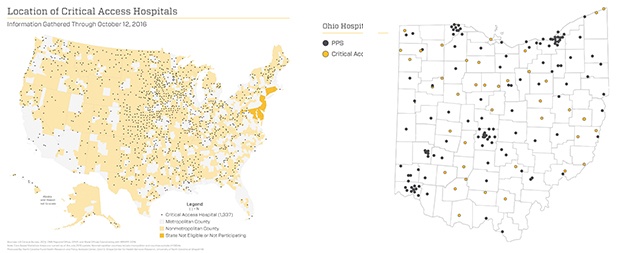

In Ohio, the AMA lists 33 hospitals with Critical Access designation. This is relatively low since Wisconsin has 58 and Kansas tops the charts with 84 (see the national map showing all the CAHs below). To visualize my home state of Ohio better, I created the other graphic below. This state map with county outlines shows all of the Acute Care Hospitals in Ohio (black) and the CAHs in yellow. If I use the governmental figures, Ohio comprises 183 non-federal short-term acute care facilities, of which 33 are Critical Access. This makes our percentage in Ohio 22.4%, a little lower than the national average. Of these, there are 1,244,593 admissions accounting for 5,568,232 patient days and net revenue generation of $111,549,393. (https://www.ahd.com/state_statistics.html)

Design Considerations

The Facility Guidelines Institute, in the latest version of guidelines, includes provisions for CAHs. Recommendations were made for issuance in the 2010 edition; however, they were late in including CAHs in 2010. The latest version of the 2014 FGI standards adopted the drafts released in April 2011. As part of those recommendations, the latest guidelines have chapters dedicated to Children’s Hospitals (2.7), Cancer Care Facilities (3.6), Dental Facilities (3.14) and Critical Access Hospitals (2.4).

Since beds are one of the main constraints on the facility, acuity-adaptable beds are important as they allow for maximum flexibility per census. As mentioned above, a CAH is limited to 25 inpatient beds; however the acuity (critical, intermediate, and acute care) is not mandated. CAHs do provide intensive care services, a fact of which not everyone is aware. CAHs may also provide observation beds, which do not count toward the 25-bed limit as long as they truly function in this role.

Additionally, a CAH may have psychiatric bed/rehabilitation and skilled nursing beds as separate Distinct Part Unit (DPU). DPU is a CMS designation requiring these beds to be physically distinct from the hospital, and fiscally separate for cost reporting purposes.

Currently, as stated above, many of these facilities operate on such thin margins, that even the slightest change in federal reimbursements could cripple them financially. Nearly 60% of gross revenue comes from government agencies, including Medicare (44.4%), Medicaid (14.0%) and other government payers (1.2%). Revenues from private payers usually do not cover their costs, which makes them very susceptible to closure if governmental reimbursement structures change.

In the past few years, I have seen several CAHs either go out of business, or purchased by larger systems. Some have even been forced to drop important services, requiring people in their communities to drive hours elsewhere to access care. One CEO was telling me that insurance agencies have forced many of his people into larger systems in other cities for imaging, tests and other ancillary services, which put a financial strain on the facility. Actions like this go directly against the protections provided so that these facilities remain viable to serve the people in that area. Apparently, they are required to do more with even less. This is why I want to work more closely with the leaders of these organizations to help them navigate operational and facility constraints.

Blog authored by Andy Vogel, a former principal with Array.