Originally published in Medical Design & Construction.

Healthcare systems are challenging the value of delivery of care versus facility ownership and management. Many are questioning initial capital investments that add to a stable of a depreciative real estate and are looking to enter into build‐to-suit, long‐term lease agreements in another owner’s building. New medical office buildings, including outpatient facilities in dense urban environments, are trending toward this evolving model of developer‐led buildings.

The developers of these projects are realizing the value of quality projects and investing in high-performing building envelopes, focused on reducing operating costs while simultaneously creating comfortable environments for the occupants of the building. To protect investments, developers are not only adding specialized façade consultants to the base project team, but also challenging architects to create high-performing, innovative buildings.

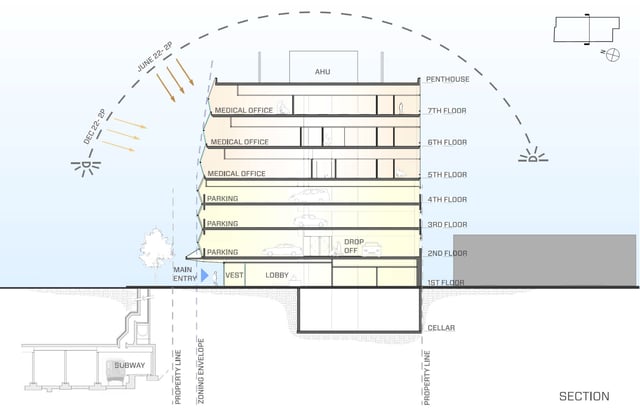

A new seven‐story medical office building located in Brooklyn, New York, looks to explore dynamic and innovate ways of designing building enclosures. The new facility is approximately 75,000 SF of building program on floors 1, 5, 6 and 7 with a 200‐car, three‐story, open-air parking garage on levels 2, 3 and 4. The site is a half city block in length and spans the width of a full city block. The building will be the tallest structure within a mile, promising phenomenal views to the north and east, as well as four sides of solar exposure.

The team began the design by optimizing the building massing and orientation on the site, looking at options to balance the critical issues of zoning, project program and long‐term site utilization. Medical office buildings are by nature programmatically‐driven buildings requiring a high degree of flexibility, allowing the building over time to be modified to meet the needs of volume changes in service lines. Array studied several options, looking at various massing options, amounts of perimeter exposure and site density. We also studied the site so future phases could be added, providing further flexibility to the building program.

The team began the design by optimizing the building massing and orientation on the site, looking at options to balance the critical issues of zoning, project program and long‐term site utilization. Medical office buildings are by nature programmatically‐driven buildings requiring a high degree of flexibility, allowing the building over time to be modified to meet the needs of volume changes in service lines. Array studied several options, looking at various massing options, amounts of perimeter exposure and site density. We also studied the site so future phases could be added, providing further flexibility to the building program.

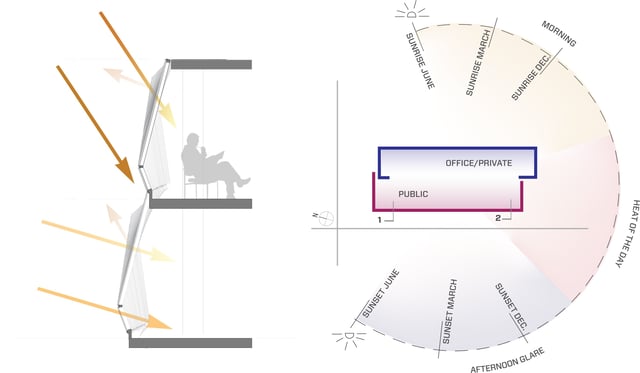

When buildings are oriented with their long axis in the east‐west direction, the broad face of the façade faces south, where typically the high angle of the sun can be dealt with by window setbacks or horizontal shading devices. In urban environments, with fixed street grids, the building orientation cannot always match the configuration with optimal solar exposure. Medical office buildings are similar to other office buildings in that, programmatically, they have many spaces with a qualitative affinity toward access to natural daylight; this is a key driver in buildings that are perimeter driven. The difference, however, is that treatment and exam spaces along the perimeter of a medical office building have greater privacy issues and tend to want higher windowsills. The low angles of the late afternoon westward light are often problematic from a heat gain and glare perspective.

Strategic planning of the building’s clinical and public zones helped reconcile the types of spaces adjacent to a particular solar exposure. Solar analysis indicated that the east façade only received direct sunlight until the late morning. This combined with a higher spandrel‐to‐glazing ratio with a design that incorporated higher window sills, allowed the design team to select a glazing with a higher visible transmittance and higher solar heat gain coefficient (SHGC), permitting a little more heat gain in the early morning and maximizing the amount of natural ambient daylight in the treatment, exam and conference spaces of the building. The additional daylight provides a high level of visual clarity benefiting the care provider while mechanically, the higher SHGC on the east façade permits additional heat gain in the morning helping the building to ramp up to temperature.

The west side of the building takes advantage of the views by placing all public waiting spaces along the elevation. In considering floor‐to‐ceiling glass along this façade, the design team had to look for ways to deal with heat gain and low-angle glare late in the afternoon. Several iterations of façade geometry were studied, looking at different ways to fold the façade so the building could cast a shadow on itself under certain solar conditions.

A diagonally-folded, horizontal façade was determined to provide a solution that maximized glazing and mitigated solar gain. Glazing with a low SGHC and high exterior reflectivity were chosen for the west façade to reduce solar gain. This solution reduces the cooling demands and lowers projected operating costs. Additionally, the waiting spaces along the west side of the building have a higher level of thermal comfort for the patients and visitors. Fifty percent of the glazing on the west façade slopes upward toward the direction of late afternoon sun. The other half of the exterior wall is sloped downward away from the sun to effectively be in shadow the majority of the day.

The design team performed a foot-candle analysis to further determine the exact specification of glazing adjacent to the waiting spaces in the building. Several iterations of illuminance studies were carried out with different glazing performances, allowing greater accuracy in the glazing selection.

The team looked at several options, which would reduce the intensity of solar gain while maximizing visible transmitted light. The net result was a reduction in direct artificial lighting.

When this building is complete in 2018, the team intends to compare actual energy costs at different times of the year to learn more about the performance of the building and the materials specified.

Blog written by Tony Caputo, former designer with Array Architects.