Featured in Medical Design & Construction, January/February 2017.

While no one would argue against the clinical benefits that the private patient room model yields, it’s worth pausing to analyze the physical forms that are natural offsprings of current code mandates and operational practices. As our designs rapidly evolve to keep pace with industry changes, we must not forget elements that have time-tested effectiveness in improving the physical and mental well-being of the patients and staff that inhabit these environments.

For a wide variety of operational reasons, the most prevalent layout for patient units today is a single-loaded corridor with central core support spaces, commonly referred to as the “racetrack” or “ring road” model. The drivers that have moved the industry to this configuration include minimizing the increased travel distances resulting from single-occupancy rooms, as well as the need to locate work areas and supplies closer to patients and caregivers. Though this model may be optimally efficient, its evolution caused some historical patient unit features to become less common, one such feature is the patient lounge, also known as the solarium.

In the days of patient wards, having a refuge away from the crowds and chaos, where patients could get fresh air and sunlight, was a basic component of patient care, not to mention one of the only “amenities” available to patients. During the semi-private room era, the patient lounge became a place for patients and their families to find a bit of solitude and privacy away from their roommates. While private rooms have all but eliminated the need for these spaces from the patient care perspective, as they have disappeared from (or taken less prominence in) industry standards, there have been some residual impacts we should address.

While not their primary intent, patient lounges frequently allowed natural light to penetrate more deeply into the interior circulation and work spaces of the patient unit, providing some relief to what could be challenging work environments. As we design in the era of Lean-led process optimization, it can become expedient, and habitual, to view elements that aren’t operationally compulsory as part of the “waste” that we need to eliminate.

It’s imperative that we understand and place proper import on the psychological and performance benefits of designing deep natural light penetration into the patient unit core. In no particular order, here are my top five evidence-based, data-driven reasons for daylighting work areas within patient units:

Employee Satisfaction

Satisfaction levels increase when workers are near windows. Dr. Kjeld Johnsen, of the Danish Building Research Institute, reported that not only did individual satisfaction improve with proximity to windows but also that the converse negative effects of increasing the distance from windows were greater as the number of people in the space increased, a significant concern in centralized team station models.

Physical Health and Wellness

Exposure to daylight can significantly contribute to the overall health of building occupants. Studies have shown benefits including:

- Improved sleep—workers who have windows sleep an average of 47 minutes more per night

- Lower obesity risks—daylight exposure has been correlated with reduced BMI and enhanced self-control

- Reduced blood pressure by altering levels of nitric oxide in the skin and blood

- Reduced heart attack risk

Mental Health and Wellness

Exposure to daylight stimulates the body’s production of mood-enhancing hormones. Scientists have linked increases in beta-endorphin, the “feel-good” molecule; cortisol, the “anti-stress” hormone; and melatonin, the “circadian regulator”, to exposure to natural light.

Employee Productivity

Studies have also found a correlation between Increased work quality and increased daylight exposure. Linked to the positive moods outlined above are corresponding increases in problem-solving, creative thinking, learning and socialization that improve the quantity and accuracy of work.

Sustainability

Daylighting can minimize the reliance on artificial lighting while helping to reduce energy consumption. Despite all of the good the improved energy codes mandate, hospitals are still energy hogs. The energy use intensity of a hospital is nearly three times that of a typical office building. The U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Federal Energy Management Program reports that effective daylighting can reduce lighting energy use in building interiors by up to 75%.

Daylighting’s effectiveness at reducing energy consumption and improving workplace quality is acknowledged by both the USGBC LEED rating system (IEQ Credit 8.1: Daylight and Views – Daylight) and the Well Building Standard® system (Well Building Standard for Light credits 54 – Circadian Lighting Design, 61 – Right to Light, 62 – Daylighting Modeling, and 63 – Daylighting Fenestration).

One project that is illustrative of our approach to addressing this issue is a Greenfield hospital we are currently designing in southern New Jersey. From the outset, this project was conceptualized as an instrument tuned for process efficiency, but as we progressed through the initial planning and design, we weighed the unit plan’s compactness against the environmental quality of the central core work areas and began exploring methods to balance the two.

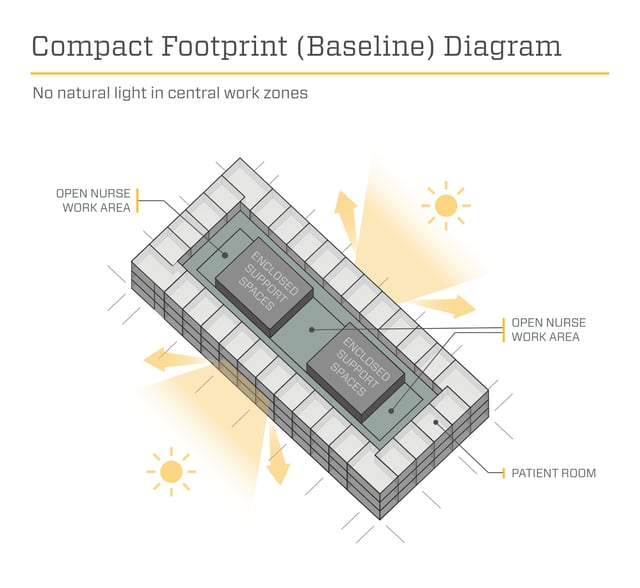

Initially, we applied a universal planning grid overlay on a 32-bed racetrack concept to create a baseline for our analysis. While this layout may result in the lowest caregiver footstep count, this exercise quickly revealed both the atmospheric compromises and support space shortcomings that were a natural outcome of prioritizing process over the environment.

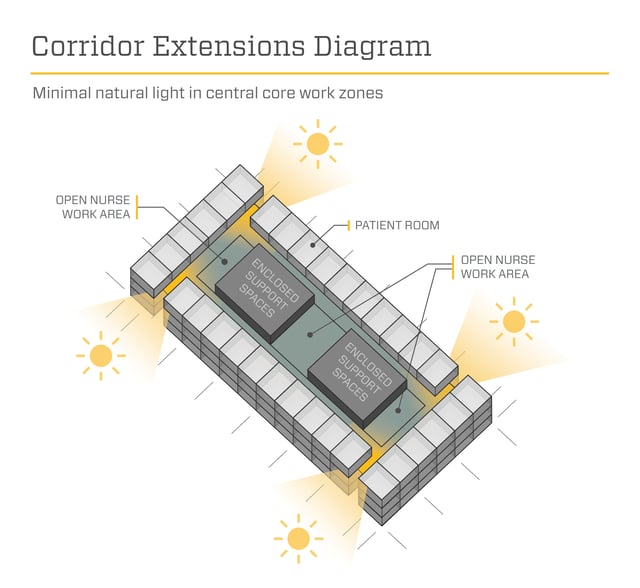

Next, we tested the effectiveness of eroding the building corners to provide windows at the corridor ends. Though we felt this was an effective solution from a compactness/efficiency and wayfinding/corridor environment perspective, we didn’t feel it realized an equitable work environment solution, since the corner glass really didn’t penetrate far or wide enough into the unit to be universally effective.

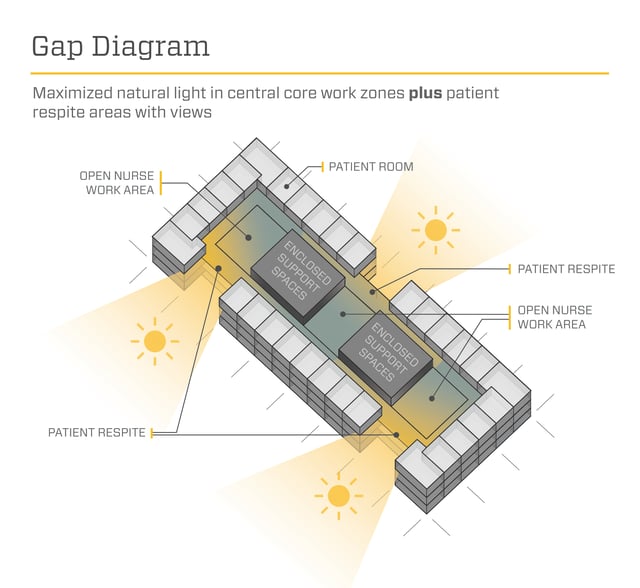

The solution we finally settled into integrates three “gaps” in the perimeter patient rooms. We positioned these gaps on alternate sides of the building so that they are equally spaced along the racetrack, and integrated a semi-decentralized team station model at these gap points. Additionally, the three team work zones span the entire central support core so that natural light penetrates all the way through the unit. Finally, we provided sufficient clearances at the gaps to allow for intimate seating groups along the floor-to-ceiling glass.

Although this solution increased the building length by one structural bay (approximately 30 feet), we made this strategy area neutral. In our, and our client’s, evaluation, this solution became a “no cost” way of achieving a quality work environment for their staff that will have a lasting, positive impact on patient care and the system’s bottom line.